Physics Heroes & Heroines: Black History Month

February is Black History Month in the U.S., a time to spotlight the experiences, achievements, and contributions of African Americans. Continuing Radiant's ongoing series on Physics Heroes & Heroines, we dedicate this post to recognizing some notable Black scientists who've had an impact. In past posts, we've also spotlighted African American physicists Elmer Imes and Shirley Jackson.

Gladys West (1930 - )

Anyone who's ever used GPS technology for navigation has Gladys West to thank. She was born in 1930 to sharecropper parents. Her scholastic abilities soon took her from valedictorian of her high-school class to a scholarship at Virginia State College (Now Virginia State University), where she earned a bachelor's in mathematics and, after teaching for a few years, a Master's degree.

She was hired in 1956 by the U.S. Naval Proving Ground, a weapons laboratory, demonstrating skill at solving complex mathematical equations by hand. When computers came along, she moved into programming, working on high-profile projects for the Navy. In 1960, she participated in an award-winning study of Pluto's planetary motion in relationship to Neptune. In 1978 she became project manager for Seasat, the first surveillance satellite used to collect data on oceanographic conditions and features.

"Out of West’s work on Seasat came GEOSAT, a satellite programmed to create computer models of Earth’s surface. By teaching a computer to account for gravity, tides, and other forces that act on Earth’s surface, West and her team created a program that could precisely calculate the orbits of satellites. These calculations made it possible to determine a model for the exact shape of Earth, called a geoid. It is this model, and later updates, that allows the GPS system to make accurate calculations of any place on Earth."1

(Image: Gladys West in 2018, being inducted into the U.S. Air Force Hall of Fame. )

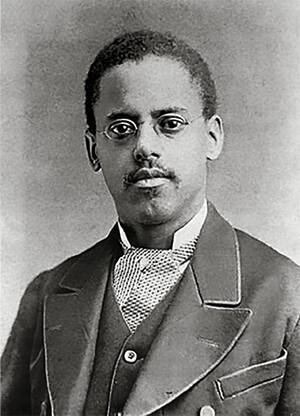

Lewis Latimer (1848 - 1928)

Born in Boston in 1848 to parents who had escaped from slavery, Lewis joined the Navy when he was just 16 and fought for the Union army in the Civil War. After earning an honorable discharge, he went to work for a patent firm, where he became fascinated with mechanical drawings and learned to be a skilled technical draftsman. He was hired by Alexander Graham Bell to draw the blueprints for a new invention, the telephone. He went to work for an electrical lighting company becoming expert on the new field of incandescent lighting and patenting a new filament for the light bulb that used carbon for the filament, which increased the life span of light bulbs (previously they would die after just a few days of use).

Latimer was eventually hired by Thomas Edison. "Edison encouraged Latimer to write the book, Incandescent Electric Lighting: A Practical Description of the Edison System. Published in 1890, it was extremely popular as it explained how an incandescent lamp produces light in an easy-to-understand manner. On February 11, 1918, Latimer became one of the 28 charter members of the Edison Pioneers, the only African-American in this prestigious, highly selective group."2

In his later years, he taught mechanical drawing, engineering, and English to new immigrants. remained active in patriotic activities as "an officer of the famed Civil War Veterans' organization, the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR). In addition, he supported the civil rights activities of his era."2 He was called a "Renaissance Man" due to his wealth of talents, with a book of his poetry published by his children in 1925.

(Image: Lewis Latimer 1882, Photo courtesy of Queensborough Public Library)

Patricia Bath (1942 - 2019)

Human vision is at the core of what we do at Radiant: photometry is the science of how humans perceive light. Patricia Bath is an ophthalmologist who developed a breakthrough laser technique to treat cataracts and blindness. Spurred by a childhood interest in science, she studied to became a medical doctor—in 1969 becoming the first Black person to study Ophthalmology at Columbia University. "When she was just out of medical school, working as an intern at Harlem Hospital and then at an eye clinic at Columbia University, she noticed discrepancies in vision problems between the largely Black patient population at Harlem and the largely White one at Columbia. Her observations led her to document that blindness was twice as prevalent among Black people as among White people — findings that instilled in her a lifelong commitment to bringing quality eye care to those who might not otherwise have access to it."3

Black people were also eight times more likely to develop glaucoma. To improve access for underserved patient communities, she founded the American Institute for the Prevention of Blindness in 1976, which established that 'eyesight is a basic human right.' She was the first woman (of any color) to join the Department of Ophthalmology at UCLA’s Jules Stein Eye Institute.

She went on to develop new treatments for eye issues, receiving patents for five different inventions. Her most famous patent was granted in 1988 for the Laserphaco Probe, a less painful and more effective treatment for cataracts. It was the first medical patent ever granted to an African American woman doctor. "With her Laserphaco Probe, Bath was able to help restore the sight of individuals who had been blind for more than 30 years. The device is used worldwide and has improved the vision of millions of people."4 Some of her other inventions use ultrasonic pulse and laser technology for treating cataracts.

(Image: Patricia Bath at an awards event at the Tribeca Film Festival in 2012. Jemal Countess/Getty Images)

CITATIONS

1. Matthias, M., "Gladys West: American Mathematician." Britannica.com (Accessed February 13, 2024)

2. George, L., "Innovative Lives: Lewis Latimer (1848 - 1928): Renaissance Man." Smithsonian, National Museum of American History, Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation. February 1. 1999.

3. Genzlinger, N., "Dr. Patricia Bath, 76, Who Took on Blindness and Earned a Patent, Dies." New York Times, June 4, 2019.

4. Patricia Bath, Biography.com (Accessed February 13, 2024).

Join Mailing List

Stay up to date on our latest products, blog content, and events.

Join our Mailing List